Mohammed VI may still have a long life ahead of him, but a sense of the end of an era has already taken hold in the kingdom. Barring unforeseen events, he will leave his son, Moulay Hassan, a stable country and an authoritarian regime boasting numerous diplomatic successes.

Ignacio Cembrero, El Confidencial, 31/12/2025

Translated by Ayman El Hakim

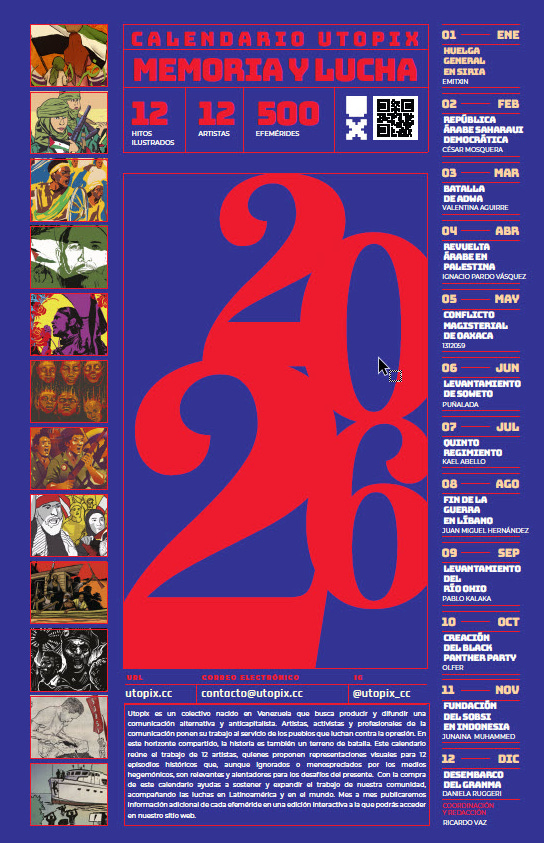

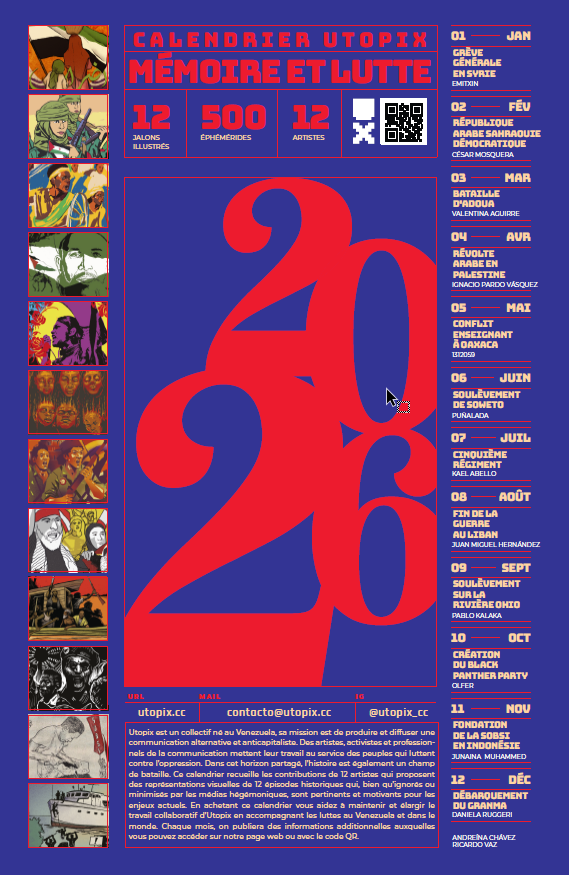

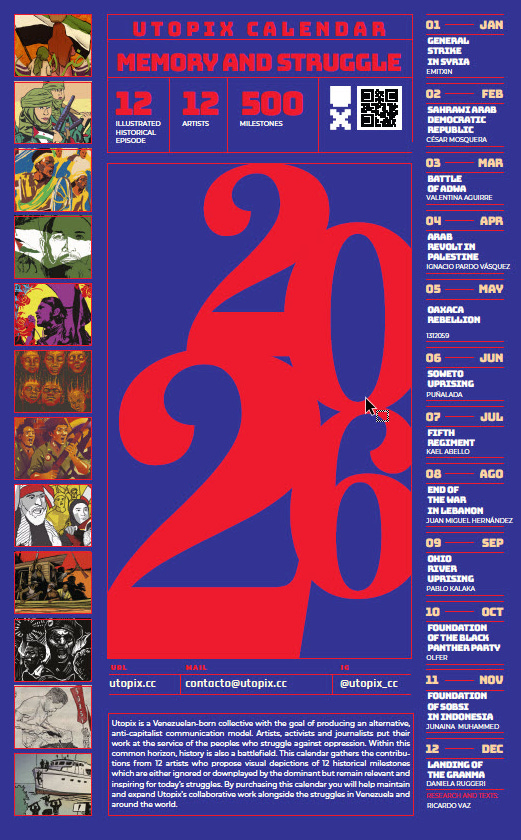

Ilustration: EC Diseño

Morocco is already experiencing a phase marking the

end of a reign. It is not that King Mohammed VI, aged 62, is gravely ill or

that his days are numbered after twenty-six long years on the throne. Yet

dynastic succession has become a topic of conversation among Casablanca’s

bourgeois circles, while subtle movements can be observed among officials

seeking to position themselves more advantageously when a new king ascends the

throne.

Although his portrait is everywhere, Mohammed VI has

never been very present in the life of his country. Between his long holiday

stays abroad, periods of convalescence and recurring ailments, the sovereign

became known as “the missing king”, as described in

2023 by the British weekly The Economist.

He was not even present on Sunday the 21st at the

inauguration in Rabat of the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON), the biggest

sporting event held in Morocco in years. He began his holidays in Abu Dhabi on

5 November, continued them in Paris and Cairo, and was still extending them

last weekend, even though official propaganda portrays the tournament as “the

spark of Morocco’s general rebirth”. He delegated the ceremonial kick-off to

his son, Moulay Hassan.

The collective awareness of Mohammed VI’s frailty may

have crystallised in late October 2024, when he travelled to Rabat airport to

welcome French President Emmanuel Macron. He appeared extremely thin, leaning

on a cane and walking with difficulty. The official explanation for the use of

the cane failed to convince many observers.

When Mohammed VI eventually passes away, Morocco will

undergo a transition without upheaval. The king has an undisputed heir: Moulay

Hassan, 22, his only son. Little is known about him, as the royal palace has

not even communicated about the progress of his studies at UM6P, a private

university. In theory, he is less well trained than his father, having neither

completed a doctorate nor undertaken internships in international

organisations. Nor has he been entrusted with many representational duties.

He did, however, receive Chinese President Xi Jinping

in November 2024 during a technical stopover in Casablanca. The king was once

again on holiday at the time. That episode remained an exception. The following

month, it was Moulay Rachid, Mohammed VI’s brother, who represented the monarch

at the reopening of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, attended by the world’s

elite.

Some of the heir’s personal inclinations have

nevertheless become known. He is very close to his mother, Princess Lalla

Salma, 47, from whom Mohammed VI separated in March 2018. He lives with her and

his sister, Lalla Khadija, 18, in the Dar Es Salam palace; he endured the

painful divorce at her side; and he goes on holiday with her to Courchevel in

the French Alps or to Mykonos in the Aegean Sea. When he accedes to the throne,

this information-systems engineer will exert considerable influence over the

new king.

When the time comes, Mohammed VI will leave his

son—provided no unforeseen and undesirable events occur—a well-established

kingdom. Despite deep social inequalities, Morocco is the most stable country

in all of North Africa, more so than Algeria despite its gas and mineral

wealth. This stability stems from the monarchy’s role in structuring the

country both politically and religiously.

Mohammed VI’s escapades—his holidays stretching to

nearly six months in some years, his close friendship with three

German-Moroccan mixed martial arts (MMA) fighters with whom he lived in the

palace, or his unsteady wanderings with a drink in hand during a Parisian night

in August 2022—have even trended on social media.

They have prompted a flood of mocking or scandalised

comments about his person, yet without eroding the monarchical institution. Not

even the major Moroccan Islamist movement Justice and Charity (Al-Adl

wal-Ihsan), illegal but relatively tolerated, took advantage of the situation

to attack the Commander of the Faithful, the religious title also held by the

king.

Over time, Mohammed VI has become more cautious. After

having allowed the Azaitar brothers, the MMA fighters, for years to decide who

among the royal family could visit him in his private quarters and at what time

of day, he has now relegated them to the background. They no longer appear at

his side nor flaunt their luxury gifts—Rolex watches or Ferrari and Bentley

cars—on social media.

Since the summer of 2022, his main companion has been

Yusef Kaddur, 41, a Spaniard from Melilla and also a martial-arts expert.

Unlike the Azaitars, he is discreet and modest, but equally uneducated. When he

still lived in Melilla, he wrote on Facebook riddled with spelling mistakes. He

does, however, help lift the monarch’s spirits when he is feeling down. Kaddur

enjoys the esteem of the royal family.

The respect—or fear—inspired by the king is such that

protesters do not even dare mention him. The young activists of the GenZ212

movement, who took to the streets in September to demand better education and

healthcare, criticised the government headed by billionaire Aziz Akhannouch.

They never targeted the monarch, even though many of the decisions later

implemented by the government are taken within the royal palace.

Today, youth mobilisations, jihadism, political Islam

or a nearly non-existent left pose no threat in Morocco to the monarchy or to

the courtiers—sometimes referred to as the “makhzen”—who gravitate around it.

Hence the incomprehensible scale of repression exercised, for example, against

those who responded to the GenZ212 call. In the autumn alone, 5,780 arrests

were made; around 2,480 protesters have been or will be tried, and 1,473 are

already behind bars, including some 300 minors.

These and many other episodes make it clear that

Morocco is not on a path toward a parliamentary monarchy, contrary to what

figures such as Omar Azziman once suggested when he was ambassador to Spain

(2004–2010) before becoming a royal adviser.

When Mohammed VI ascended the throne, there were no

Moroccan prisoners of conscience—only Sahrawis—because his father, Hassan II,

had relaxed repression at the end of his reign. A quarter of a century later,

many are behind bars, starting with the four leaders of the peaceful Rif

uprising (2016–2017) and Mohamed Ziane, 82, Africa’s oldest political prisoner.

This former human-rights minister under Hassan II dared to suggest in a video

that, given the king’s frequent absences, abdication might be preferable. Ziane

holds dual Moroccan and Spanish nationality, his mother being from Málaga.

Winds of freedom gradually stopped blowing in Morocco

from 2003 onwards, following the jihadist attacks in Casablanca (33 dead). They

briefly returned during the fleeting “Arab Spring” in early 2011, but another

terrorist attack, this time in Marrakech (17 dead), put an end to the opening.

Authorities tightened the screws again in 2020, after the pandemic, to silence

the last dissenting voices, starting with the finest pens of independent

journalism, who ended up in prison. They were pardoned in 2024, but are barred

from practising their profession.

Only the massive peaceful demonstrations against the

invasion of Gaza and Morocco’s close relations with Israel escaped repression.

They were called by the Moroccan Front for Solidarity with Palestine and other

associations discreetly supported by Justice and Charity Islamists.

Public indignation was such that the authorities did

not dare ban them, yet they did not scale back cooperation with the Hebrew

state, which has become a strategic partner. The truce in Gaza has brought

relief to Moroccan authorities.

“Morocco has moved from the dictatorship of Hassan II

to the enlightened autocracy of Mohammed VI,” Le Monde summarised in a six-part

series published last summer on the Moroccan monarchy. The autocrat is not

alone. He is supported by a very small circle of collaborators, among whom

Fouad Ali El Himma, 63, sometimes dubbed the viceroy, stands out. A former

schoolmate of Mohammed VI at the Royal College in Rabat, he often holds the

reins of a country whose head of state periodically disappears.

He intervenes in all areas, but has a particular

fondness for the massive domestic security apparatus, in which he worked from

1999 to 2007, headed by the kingdom’s top policeman, Abdellatif Hammouchi,

architect of the use of the Pegasus spyware. He also plays a role in foreign

policy, implemented by Nasser Bourita, Mohammed VI’s most influential foreign

minister.

For the first time this century, cracks have appeared

in the counter-intelligence and secret-police machinery, tasks overseen by the

General Directorate for Territorial Surveillance (DGST), under Hammouchi and

ultimately under El Himma’s supervision.

From a mysterious Telegram channel, a hacker group

called Jabaroot revealed in August personal data relating to several senior

DGST agents, including their real-estate holdings. Among them was the agency’s

de facto number two, Mohamed Raji, nicknamed “Monsieur Wiretaps”, who has

headed telephone surveillance for over thirty years and carried out assignments

for the king himself.

The flight abroad of Mehdi Hijaoui, former number two

of the General Directorate of Studies and Documentation (DGED), also reveals

unease within the foreign-intelligence agency. With far fewer staff than the

DGST, it nevertheless operates with a larger budget. Some signs also point to

friction between domestic and foreign intelligence services, without this

having undermined the country’s security.

The one area where everything has run smoothly is

foreign policy, which is almost monothematic. More than one hundred countries

now support Morocco’s three-page autonomy plan—currently being fleshed

out—offered since 2007 for Western Sahara. Two major democracies, the United

States and France, have gone even further by recognising Moroccan sovereignty

over a territory the UN still considers non-self-governing and awaiting

decolonisation.

The culmination of this wave of diplomatic successes

came on 31 October, when the UN Security Council adopted, without a single vote

against, Resolution 2797, establishing the Moroccan autonomy proposal as the

basis for future negotiations. This endorsement is all the more significant as

it was driven by the administration of President Donald Trump, backed by

France. A third power, Israel, completes this triumvirate of support for

Morocco.

“This accumulation of diplomatic victories is all the

more striking given that they are achieved by a country whose head of state

constitutionally wields almost all power, yet is frequently absent,” marvels a

European official who served for many years in Rabat.

This backing from the UN’s highest body does not by

any means put an end to the Sahara dispute, which erupted half a century ago

when Spain handed over its colony to Morocco and Mauritania. It will, however,

lead to the resumption of negotiations. As long as Algeria resists Western

pressure and continues to support the Polisario Front, which it hosts in the

southwest of its territory, the conflict will persist, albeit at low intensity.

Rabat may even decide in the medium term to bring this

latent confrontation to the surface, at the risk of igniting the region. One of

its objectives, viewed favourably by Washington, is to force MINURSO, the small

UN mission that has long ceased to fulfil its role, out of Western Sahara. If

that were to happen, Morocco would be tempted to exploit its military

superiority to seize the eastern strip of the former colony—20 % of the

territory (50,000 km²) that it does not control and through which the Polisario

operates.

“With or without an agreement, and with US approval,

Morocco will decide, when the time is right, to annex those areas east of the

wall that belong to it,” predicted Abdelhamid Harifi, administrator of the

unofficial forum Royal Armed Forces–Morocco. “It would then take only two or

three weeks,” he stressed. How would Algeria react? Would it go to war to try

to prevent it and save its protégé?

The Sahara is not the only arena of confrontation

between Morocco and Algeria. Moroccan diplomacy is also exploiting Algerian

setbacks in the Sahel to advance its own agenda. The most striking example is

the offer, made by the king himself, to give Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali

access to the sea via the port under construction in Dakhla (formerly Villa

Cisneros) in Western Sahara.

The project, which ignores Mauritania, is somewhat

far-fetched, like the 6,000-kilometre gas pipeline linking Nigeria to Morocco.

They are unlikely to materialise, but in April Mohammed VI was already

photographed in Rabat with the foreign ministers of those three countries, once

protégés of Algiers. Morocco is now the one expanding its soft power in parts

of the Sahel. It even successfully mediated in December 2024 to secure the

release of four French spies imprisoned in Burkina Faso.

All these Moroccan achievements carry a more troubling

reading for Spain. No sooner had the Security Council resolution been adopted

than Moroccan diplomacy publicly laid out its claims vis-à-vis its Spanish

neighbour, via Atalayar, the unofficial mouthpiece of the Moroccan lobby in

Spain, and Media24, the digital daily closest to Foreign Minister Nasser

Bourita. “They are emboldened,” more than one Spanish diplomat remarked at

year’s end.

In its effort to extract concessions from Spain while

offering little in return, “Morocco uses instruments that are not strictly

military to consolidate strategic objectives, such as asserting its sovereignty

over Western Sahara,” recalls Alejandro López Canorea in his newly published

book La Guerra del Estrecho [The War of the Strait].

“All this amounts to a form of hybrid warfare that does not necessarily involve

the outbreak of open conflict, but rather a deep-seated, sustained

confrontation waged with non-conventional tools,” the author explains.

Irregular migration is Rabat’s preferred instrument,

used with particular brazenness in May 2021, when it encouraged—according to

Spanish intelligence reports—the entry into Ceuta of more than 10,000

Moroccans, a fifth of them minors, in less than 48 hours. Since President Pedro

Sánchez sent his mysterious letter to Mohammed VI in March 2022, never

officially disclosed, Moroccan security forces have nevertheless worked to curb

migration flows to the Canary Islands and Andalusia, though not to Ceuta.

This effort was the only tangible quid pro quo in

exchange for Sánchez aligning himself with Rabat’s autonomy solution to resolve

the Sahara conflict. It is reversible, and Moroccan authorities could loosen

controls again whenever they deem it useful to exert greater pressure on the

Spanish government. The ambitious joint project of the 2030 World Cup, to be

hosted together with Spain and Portugal, may, however, encourage them to

postpone that moment.

Spanish military officers express another concern,

often upon retirement. “Morocco now has a very strong ally: Israel and its

technology,” recalled General Miguel Ángel Ballesteros, until two years ago

director of Spain’s National Security Department. “Originally it is not aimed

at us (…), but we must not forget that Morocco has very serious claims over

Spanish territory,” he warned. “That alliance worries me,” he concluded.

When his time comes, the young king will have to

decide whether to retain his father’s collaborators in diplomacy and security.

The former have carried out their mission successfully. The latter monitored

and curtailed his mother’s movements after the divorce, following royal orders

but increasing her suffering. They are unlikely to remain in their posts.

Who will Moulay Hassan rely on to govern? His school

and university friends lack the experience needed to advise him soundly. By

contrast, Commissioner Fouad Boutlaoui, the current head of the heir’s

security, is tipped for promotion. He harbours resentment toward Hammouchi, who

manoeuvred to have his brother, also a police officer, imprisoned.

Perhaps the best part of the inheritance the father

will pass on to the son is his fortune. Forbes last estimated it in 2015

at around €4.85 billion. From the outset of his reign, it grew exponentially,

the magazine noted. It has likely increased further over the past decade,

judging by the growing weight of Al Mada, the royal holding company, in Morocco’s

economy and its expansion into 24 countries, mostly in Africa.

The worst part of Mohammed VI’s legacy to his son is

poverty. The balance sheet of twenty years of the National Initiative for Human

Development, launched in 2005 to alleviate it, is far from satisfactory.

Poverty has declined slightly, according to studies by the High Commission for

Planning, yet 44 % of Moroccans wish to emigrate in search of better opportunities

abroad, according to the latest survey. The younger they are, the higher the

proportion.

Behind spectacular infrastructure projects—such as

Africa’s first high-speed rail line or Tanger-Med, the continent’s leading port

which has overtaken Algeciras in the Strait—lies another, less gleaming

Morocco. In his most recent Throne Speech, delivered last July, Mohammed VI

himself acknowledged this duality. “There is no room, neither today nor

tomorrow, for a Morocco moving at two speeds,” he stressed.

That should be Moulay Hassan’s great task: to achieve

harmonised growth that brings his country’s standard of living closer to that

of its southern European neighbours. Morocco’s per-capita income (€4,240 in

2025) is now seven times lower than Spain’s. Spain has around ten million more

inhabitants than Morocco, yet its GDP is ten times larger. Morocco’s total

wealth is equivalent to that of a single Spanish autonomous region: Valencia.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire